John Dunstan recalls 15 consecutive days in 1978 when temperatures in his hometown of Coober Pedy, Australia, didn’t drop below 52 Celsius (126F).

He spotted birds dropping from the sky and trees keeling over because they couldn’t survive the heat.

“As soon as you walked outside, you felt as if you were stepping into a fan-forced oven,” Dunstan, 62, said.

But, he vowed years ago never to leave the town of 2,500, where the next sign of civilisation, Port Augusta, is 540km away. It wasn’t just family loyalty that motivated him to stay. It was opal fever.

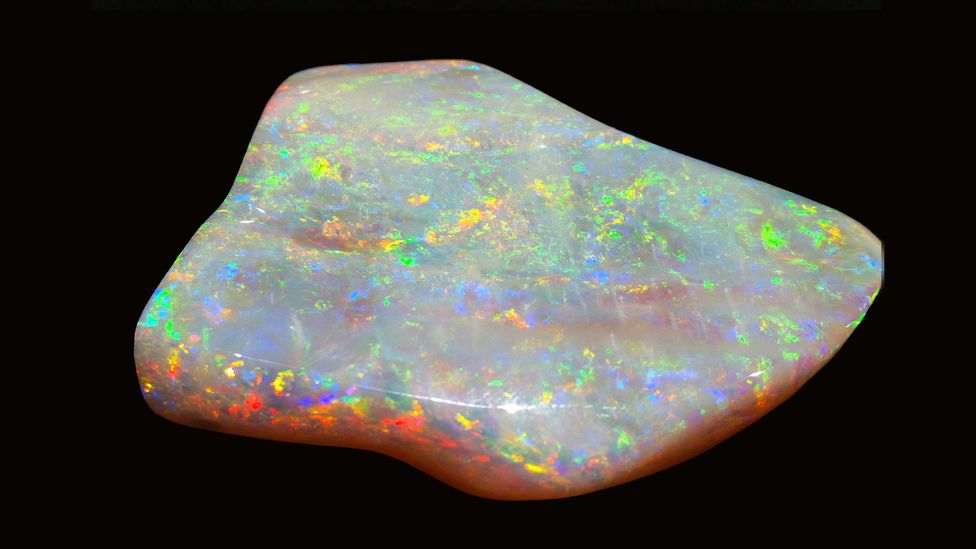

By rough estimate, Coober Pedy’s mines produce around AUD $15m ($13.9m) in opals each year, said Mining Department Program Leader Peter Lane. The figure might be much higher since many miners do not report their findings and often sell them for cash, Lane said. The majority of the world’s white opals come from Coober Pedy, reports the Government of South Australia.

A miner’s life doesn’t sound glamorous or easy, to be sure, but the attraction of the hunt, and the desire to discover that next big find, has drawn people to Coober Pedy and other mining and prospecting towns around the globe. Popular reality shows like Prospectors on US television network the Weather Channel and Dirty Jobs on Discovery Chanel Asia have made the appeal of hunting for gems and precious metals appealing to more people.

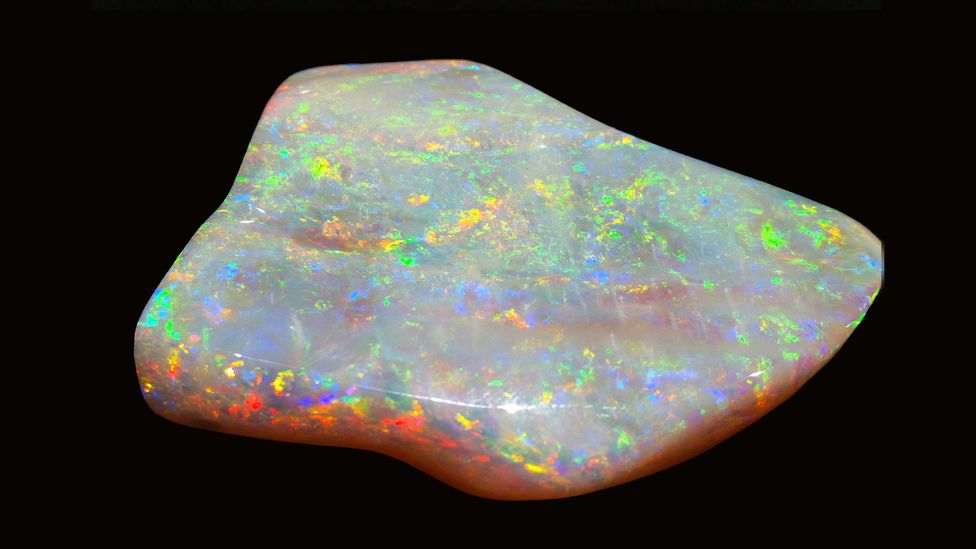

Many prospectors come to mining towns expecting to stay a few months, maybe a year. A look at the town of Coober Pedy sheds a little bit of light on why, exactly, many who come for a brief stay end up settling into a life and “career” most people never think about.

A passion for precious stones

An opal mining town since 1915, Coober Pedy has had a long history of immigrants arriving on the barren grounds eager to strike it rich. The opening of the Transcontinental Railway combined with the end of World War I turned the trickle of new miners into a boom. By the 1960s, the mining population consisted of people from 45 countries. Today, the population remains diverse, with people emigrating from countries like Hong Kong, Sri Lanka and Serbia.

Yanni Athanasiadis was one of them, leaving behind his coastal hometown of Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1972 when he was just 22. He planned to get a permit to peg his own mine then stay for one year – enough time, he imagined, to make findings worth thousands or even millions of dollars. (Opal miners aren’t paid a salary because they make money off what they find on their own). He ended up staying 42 years, and counting.

This video is no longer available

“I was hooked by opal fever. Everyday, we’d hear that someone had found ‘lots of money,’ so I strongly believed that the next day was going to be my day,” Athanasiadis said.

It’s a common story for the hundred or so estimated people who arrive each year expecting to strike it rich, Lane said. The thrill of the hunt, the potential big payouts, the independence of working for yourself on your own schedule are big attractions. The prospect of a big find draws people in and many stay, as they often do in other mining towns.

Opal mines, in particular, in the United States and Mexico tend to be smaller in scale than those in Australia. In north-central Mexico, the state of Querétaro is known as the country’s opal cradle, with fire-coloured gems embedded in its dry mountainous terrain. Many opals also come out of the arid and desolate Virgin Valley in Humboldt County, Nevada.

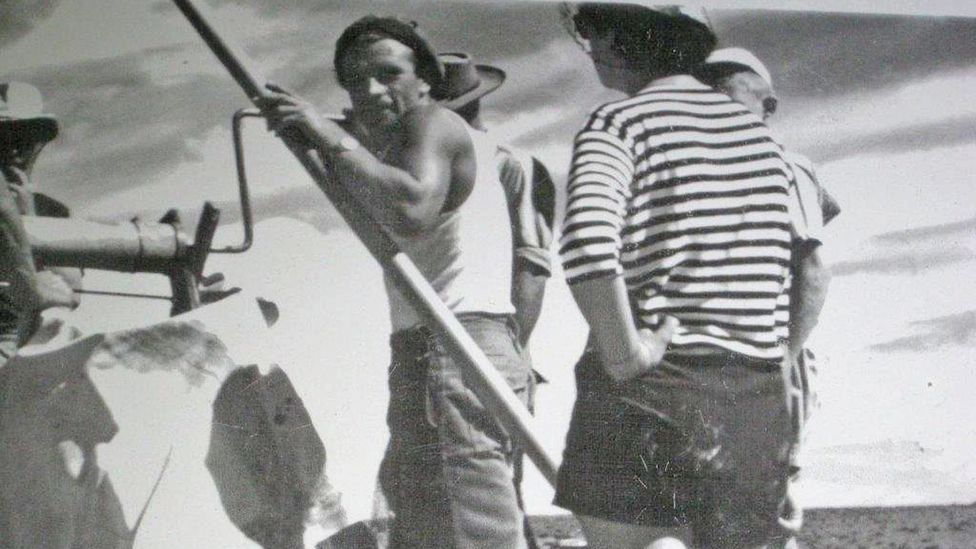

Lane said mining for other minerals like gold can be easier because seismic and aerial magnetic surveys make locating deposits easier. Made of silica, opals do not appear in these types of surveys.

“The only way to locate opal is to drill holes in the ground until you find it,” Lane said.

Once opals are located, there’s no set price like there is with gold.

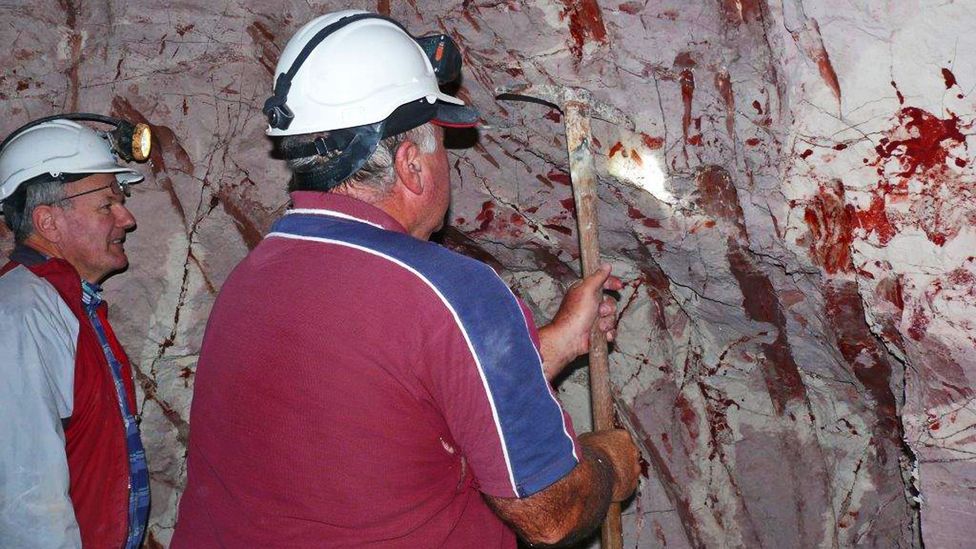

“I know people that one day were broke and next day had half a million [Australian] dollars of opals in their back pockets. So then you think, ‘nothing is stopping me from finding a million bucks,’” Athanasiadis said.

One of the biggest opal findings from the area was the Jupiter Five in 1989 by Steve Zagar, which weighed 26,350 carats. In 2003, Dunstan, also made a big find: the Virgin Black Rainbow Opal, a 72.65 carat, 120-million-year-old Belemnite fossil, which he recently sold to the South Australian Museum for an undisclosed amount.

Coober Pedy’s mines produce around $13.9m in opals each year (Desrey Jones)

Desrey Jones, Coober Pedy Tourism Officer, said each miner is required to hold a Precious Stone Prospecting Permit from the local Miners Department to gain access to small, medium or big claims. There are a few big companies in town, like Dunstan’s, but that the majority are small claims run by partnerships, Jones said. Currently, there are 260 permits operating in the area, according to Lane.

Athanasiadis continues to mine but he also owns and operates the Umoona Opal Mine Museum in town. He said running a stable, secondary business is important because, as he found out, the likelihood of sudden wealth isn’t very high. The average opal miner rakes in around the equivalent of a $40,000AUD ($37,257) annual salary over the long term, he estimates, but someone might make $180,000AUD ($167,628) in a single day with a big find, but then go years without another opal discovery.

Life underground

The daughter of opal miners, Jones grew up underground with five siblings in a five-room house. When temperatures spike or a dust storm rolls through, families like that of Jones retreat to their cool underground homes, which like half of houses in the area are built by burrowing into sandstone embankments and carving out an intricate network of rooms. These residences have all the amenities of any other house.

While living over five hours drive to the next nearest town might not sound appealing, the people of Coober Pedy have most comforts, including two supermarkets with fresh produce shipped in twice a week. Pastimes are another story.

Most homes are built underground--with full amenities--because of Coober Pedy’s extreme heat. (Desrey Jones)

“There’s not many places you can go, like in a city where there’s ice skating or the movies. You also miss out on seeing the ocean,” Dunstan said.

When Jones was a little girl, entertained herself by “noodling”, that is, pumping excess dirt up from underground and sorting through it for opals.

There are trade-offs to this simple life and the prospects of making a big opal find. Flying to Adelaide, the closest major city, from Coober Pedy’s airport will likely run you AUD $400 ($370.42) one way: the same price as a round-trip ticket from Perth to exotic Bali, Lane said. Otherwise, it’s a 12-hour bus ride or 10-hour drive. The newspaper arrives one day late, shipped in via overnight bus. The local drive-in movie theatre screens films only once every fortnight, and big blockbuster movies don’t arrive for months after their debut.

Athanasiadis’ son, Niko, who has also become a miner, thinks his dad is a bit crazy, but not because of their lifestyle. His father continues to hold on to some of the best opals he has found over the years — displaying some of them at his museum and keeping others in his safe — instead of cashing them in.

“I see a lot of opals and good ones are difficult to replace,” the elder Athanasiadis said. “ One day, I will pass them on to my son.”

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

Coober Pedy is a five hour drive from the next closest town. (Desrey Jones)

Coober Pedy is a five hour drive from the next closest town (Desrey Jones)

Coober Pedy’s mines produce around $13.9m in opals each year (Desrey Jones)

Coober Pedy’s mines produce around $13.9m in opals each year (Desrey Jones)

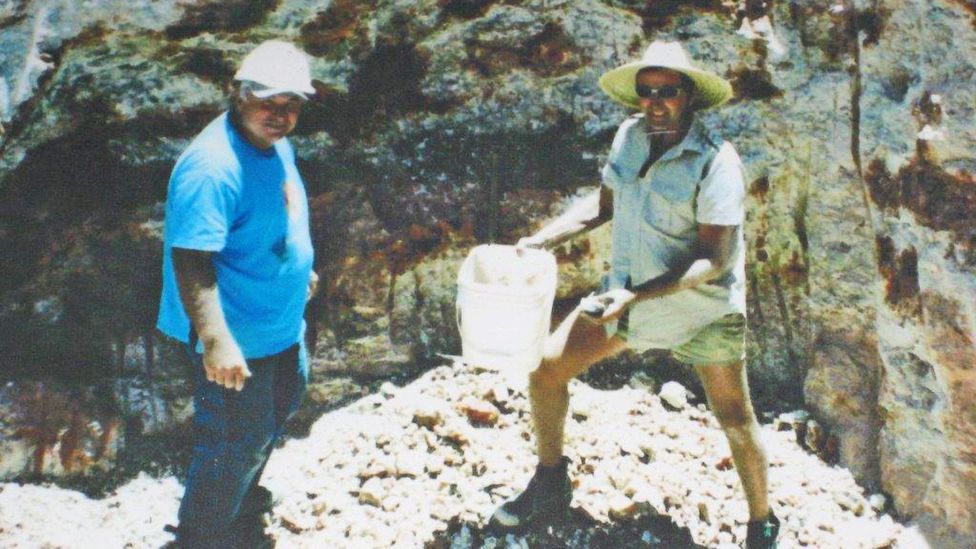

Many miners like John Dunstan's father (left) stay much longer than planned. (Dunstan Family)

Many miners like John Dunstan's father (left) ended up staying in Coober Peddy much longer than expected (John Dunstan)

Digging by hand or with small tools is preferred by many miners. (John Dunstan)

Digging by hand or with small tools is preferred by many miners (John Dunstan)

Most homes are built underground--with full amenities--because of Coober Pedy’s extreme heat. (Desrey Jones)

Most homes are built underground because of Coober Pedy’s extreme heat (Desrey Jones)

John Dunstan (left) discovered an opal worth AUD $150,000 in 2005 (Dunstan Family)

John Dunstan (left) discovered an opal worth AUD $150,000 in 2005 (John Dunstan)